By Fred J. Reyes / Philippine

Panorama, 15 April 1984

Photography: Joey

de Vera

How “Tatang”

Brought Peace and Prosperity to a Family in Nueva Ecija

In Guimba, Nueva Ecija, enshrined in a chapel beside a

rice mill, is a life-size crucifix that has drawn throngs of devotees the past

6 years. People reverently refer to the fgure on the Cross as “Tatang”.

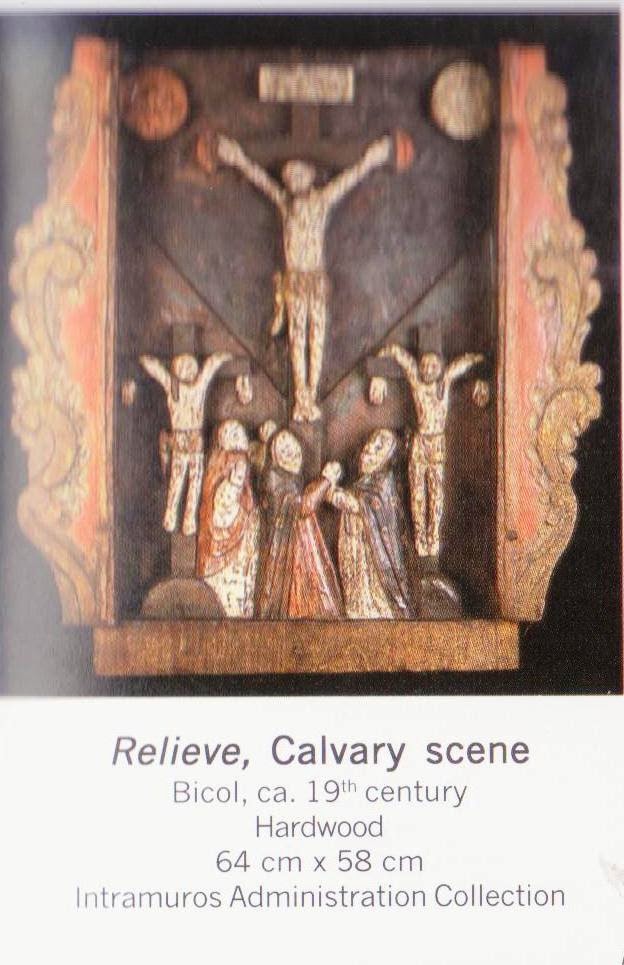

“Tatang” is no ordinary

version of the Crucifixion. Unlike most other representations of the Holy

Cross, Christ here is nailed on both wrists and feet. A block of wood juts out

between the thighs, serving as a seat and propping up the upper portions of the

body.

The most common crucifix shows Christ nailed on His palms

and His feet, and His body pressed flat against the cross.

|

| PHOTO BY JOEY DE VERA |

Some Biblical researchers say that this could not have

been the way Christ was crucified. His nailed palms, they say, could not have

been sufficient to carry the rest of His six-foot frame and would surely have

been torn loose after a short time on the cross. Thus, the seat-like projection

between His thighs, which the Roman soldiers as an afterthought, both to

prevent the palms from being torn apart and to prolong Christ’s agony.

These researchers further say that the French sculptor

who made the first such depiction claimed he had seen it in a dream. This

crucifix is said to be known in many parts of Europe as “the seated Christ”.

“Tatang”, as the

seated Christ in Guilba is beter known among residents and visitors, was

sculpted by a Filipino—Rey Estonatoc, who has a studio in Pag-asa, Quezon City.

The wooden image shows so profound a suffering that many first-timer to the

place, including wizened old men, have been seen crying unashamedly before it.

Rosario Divino Sta. Inez vda. De Santos, matriarch of the

family which owns the chapel, says Tatang

has brought peace and prosperity to her household and perhaps to hundreds of

other people since His arrival there in 1978. She is particularly thankful for

the change in the life of the youngest of her four sons, Fred, who she says was

once a black sheep of the family.

Fred, she says, used to be unemployed but also was invoLved

in some michief or other. “He used to bring nothing into the house but trouble,

all kinds of trouble”.

At the height of Fred’s youthful escapades in early 1977,

well-meaning friends succeeded in making him enter a cursillo. They had unsuccessfully tried to make him do so twice

before.

When he finally attended one, he noticed, after a few

sessions, a crucifix of the Seated Christ that had been brought into the cursillo house by a certain Delfin Cruz.

It was the first time that Fred saw such a crucifix and

his curiosity was aroused.When he asked around, one cursillista, Jose Dijamco, told him that as far as he was concerned

that was the faithful reproduction of the Crucifixion. Impressed, Fred made a

vow to have a replica of the crucifix someday.

Two weeks after the cursillo,

Fred became a changed man he ceased to be the troublemaker that his family used

to know and now went all over the barrios of Guimba doing apostolate work. In one of his sorties, a friend came up to him to offer a

wo-and-a-half acre farm for cultivation. “It was my very first job offer,” says

Fred,”and I readily accepted.”

He had just finished planting the farm to rice when a kumpadre offered him 4more hectares for

cultivation. Again, he accepted. “Kaya,

eto, umitim na ako, kakatrabaho sa bukid”., he now says, calling attention

to his deep tan.

The harvest in both farms was bountiful. He reaped 105

cavans to a hectare , which set him off to a good start in the rice business.For the first time in his life, Fred says, he found

fulfillment: “So this is how it feels to sweat and get rewarded for your own

labor”, he recalls saying to himself.

Still, something seemed lacking in his life. Often

thinking about it, he soon began to have dreams about the crucifix, sometimes

with the Virgin Mary floating with it in the clouds. When he recounted his

dreams to Dijamco, who by then had become his spiritual adviser, the latter

reminded him of his promise to acquire a replica of the Seated Christ. N Fred’s

request, Dijamco eventually found a sculptor to make one for him.

The crucifix was finished in October 1978, and Fred,

along with Dijamco and a close friend, Cris Ang, drove in a van from Guimba to

estonactoc’s studio in Quezon City to get it.“A storm was raging then”, recalls Ang. “But on our way

back, it seemed to have calmed down.”

He also remembers that the crucifix they brought back

with them attracted lots of curious (and awed) onlookers along the way, so that

they had to stop a number of times to enable people to take a close look. As a

result, it took them 8 hours, instead of the usual 3, to get back to Guimba.

The crucifix also seemed to have grown heavier, according

to Ang. Only 4 people were needed to load it into the van in Quezon City but

when they arrived in Guimba, 12 pairs of hands had to bring it inside the

chapel owned by Fred’s family.

Fred says his dream about the crucifix has never recurred

since its arrival and he now feels completely at peace with the world. “I used

to attend mass only 5 or 10 times a year and I stayed outside the church at

that. Now I remember God through Tatang every

day of the year.”

And instead of scaring people away during his days of

mischief, Fred now seems to draw people to him—people in need of help,

especially. But Fred doesn’t mind giving them help. “When you give to the poor,

you’re fulfilling the tithe required by the Church.”

His mother, Rosario, who tends a small sari-sari store

besides managing the family rice mill, says she is the happiest about the

things that Tatang has done fro her

sons and the rest of her family.

“We used to have every kind of problem, financial and

other wise,” she says. “Now all these problems seem to have vanished. We’ve

paid all our debts and sent our children to the best schools and have something

lef to buy lands and other properties.”

Here 3 other sons—Renato, Oscar and Albert, who had their

own “youthful flings” have also grown prosperous, apart from being law-abiding

and God-fearing men. Oscar, a town councilman and military officer, assists at

Mass every Sunday. A son of Fred and a son of Roberto are in the seminary,

studying for the priesthood.

Tatang, for his

part, has become something of an institution in Guimba. Every now and then,

people attribute “little miracles” to him. Sometime, in 1979, when a rift

divided the town’s cursillistas, the

statue, made of hard ipil, reportedly developed a crack on the face, from

the forehead to the bridge of the nose. The crack was said to have closed only

after the cursillistas had settled

their differences.

The chapel, while privately owned, is open to everyone, and Fred says, that like

him, countless other people may have been moved by the seated Christ to change

their ways.

He attributes to tatang all the good things that have

happened to him and his family. “He is as powerful as the man-God he

represents.”

Fred says, however, he never asked Tatang directly for the material things that he has now. “Ask him

for anything, except material things.”

All that he prayed for, Fred recalls, was faith,

fortitude and endurance in the “rat race”

of this world.