When I saw this 32 in. image of San Isidro Labrador on FB Marketplace, I thought it was an antique, crafted to perfection by an artist who seemed familiar with Spanish-style carving and religious iconography.That was until more close-up photos were shared, and I saw the still-sharp cuts and edges which bore tell-tale signs that the figure was not one. There certainly were attempts to make it look old like the effects of paint loss, missing hands, and attributes like the shovel or the sickle—symbols of the saint's work. One foot was also broken.

|

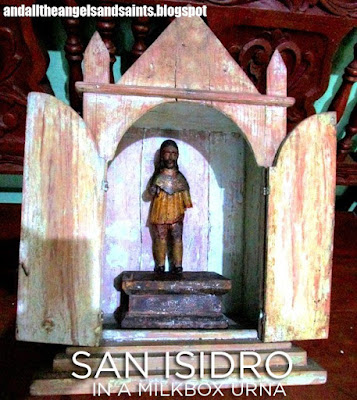

| As the santo was advertised on FB marketplace |

To

soften and smoothen the look, traces of white talcum powder can be still seen

in the crevices, mimicking dried layers of old gesso. Probably, which was why it

remained unsold for days, ignored by true-blue antique collectors.

But age to me, while important, is not always the reason why I am attracted to newer santos of this kind. It's the excellent execution of this San Isidro that got me—presented alone on a base—without the plowing angel and the kneeling Don Vargas that one often sees on tableaus. Seldom do you see vintage santos of impeccable quality such as this one.

This, surely was a product of a learned carver who knew his stuff well—from the way he accurately posed the saint with one hand on his chest, while holding, on the other hand, an iconographic farm implement, now missing.

His carved costume depicts the common outfits of peasants in old Castile: a tunic with buttons that adjusted it to the chest, short breeches, high boots (or leggings) close to the knee, and a jacket collar, sometimes decorated with a frill.

The artist paid great attention to the minute detail--from the delineation of the saint’s hair, the creases on his forehead and sallow cheeks, to his windswept hair and tunic, and the folds of his boots.

I contacted the seller and made a few inquiries; he told me the San Isidro came from Samar, and that it was carved from 2 separate woods—the base being made of santol. He asked me what my plans were—will I restore it? Repaint it? He said it looked good as is. I said I don’t know yet. I made an offer, he made a counter offer, and the deal was sealed.

In a day and a half, the San Isidro arrived at the courier’s office for me to pick up. I wasn't prepares for its weight--it was very heavy, I had to drag the huge box to my car. When I opened the box back home, there it was---San Isidro Labrador---it was exactly how I imagined it to be---except for its denseness and extreme weight ( close to 10 pounds on a bathroom scale). I was later told it was ironwood (local name, mangkono).

I was in for another surprise when a separate bubble wrap revealed his pair of hands—they were not missing after all. That, along with a broken fragment from one boot. The holes at the bottom of his feet were outfitted with short metal tubes, to provide extra support when the image was attached by pegs on the base. That rather new feature proved that San Isidro may have been made in just the last 2 years or so, new by antique collectors' standards.

I decided to make a replacement for his lost farm implement. Using found objects at home, I created San Isidro’s long-handled shovel from a rattan stick, whittled down to the right circumference, to create a pole handle. A rusty, mini-hand spade provided the metal spade, while its wooden handle was joined to the tip of the stick to serve as a handle grip. A metal strip cut from an old liquor cap was ringed around the joined parts. The long-handled shovel was distressed and aged by rolling it over the stove flame, then brushed with mahogany stain.

The santo was not without flaws, with many nicks and dings, plus the usual cracks, so I had to fix these with a variety of fillers--plastic wood for the cracks, and epoxy clay to fill in bigger gaps.

One arm and left leg of San Isidro were a bit wobbly so I had to detach them to see the problem. It turned out that the dowels or pegs used to connect arms to the body and the feet to the base have come apart. When all the parts have been secured properly, I found out one peg would no longer fit into the hole on the base; the position of one foot had moved a bit in the regluing process. I had to open up the hole and dig in a bit deeper to fix my mistake.

The whole ensemble was then polished with bees wax which evened out and darkened its color to a deep brown-black and gave it a rich mellow sheen. Though a vintage piece, San Isidro appears much better now--looking more venerable, and more valuable than ever!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)