by: Floy Quintos

Reprinted from THE SUNDAY INQUIRER MAGAZINE , October 2, 2005 issue.

Lahar spelled death for the La Naval procession in

Bacolor, Pampanga. This month, four La Sallians are bringing the tradition to

the De La Salle Campus in Dasmarinas, Cavite so that students can begin their

own tradition of homage to the Virgin.

The bucolic grounds of the Museo De La Salle in the

Cultural Heritage Complex of the De La Salle campus in Dasmarinas, Cavite, are

abuzz with student volunteers and museum personnel busy at work. Their task is

a daunting one, perhaps a bit anachronistic in a campus where most of the

students major in computer studies and nursing. They are restoring and assembling

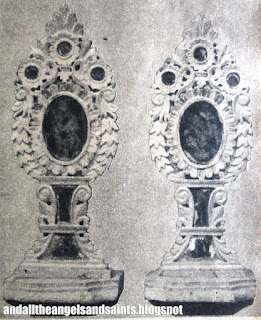

the largest extant 19th century “Carroza

Triunfal” known, a

massive yet graceful carroza of beaten silver.

For this October, the Nuestra Senora del Santissimo

Rosario de La Naval of Bacolor, Pampanga comes home to the De La Salle campus

in Dasmarinas. And here, every October from now on, she will ride forth again.

One can almost hear Nick Joaquin rhapsodizing about his most beloved of Marian

festivals.

And when she does, fours sons of De La Salle will have

fulfilled a vow to rekindle a devotion to the Naval. They are Brother Andrew

Gonzalez, FSC, two-time president of the De La Salle University System, who was

just last week installed as the first President Emeritus; Brother Edmundo

Fernandez, FSC, the youngest Brother Provincial of the De La Salle community in

the country and Brother Armin Luistro, FSC, current president of the De La

Salle University Manila and, quite recently, an active participant in national

causes.

Providing a delightful counterpoint to this august company is Jose Ma. Ricardo Panlilio, or Joey, Executive Director of the Museo De La Salle and connoisseur of all things pertaining to 19th century Philippine Illustrado style. All four come from diverse backgrounds, but share a quiet devotion spread among the De La Salle students.

For Joey, 41, the image of the Virgin and the attendant

St. Joseph, the massive and priceless carro and the very tradition of honoring

the La Naval are, at once, a remnant of childhood and a symbol of a painful

rite of passage into the real world. The image’s last custodian was his paternal grandmother, the late

Luz Sarmiento Panlilio, a grand dame of Bacolor, Pampanga, and elder sister to

the fabulous jeweler Fe.

“My

childhood was greatly influenced by Inang Lucing,” says Joey. “I

remember how the carro and the image of the virgen was the most important thing

in her life. And how the entire year centered on the preparation for the

November festival, which is when the La Naval was celebrated in Bacolor. My

brothers and I were studying in La Salle and our immediate family was based in

Manila. But every November just as the novena began, we had to come home. Inang

Lucing would ask our parents to issue excuse letters. It was important to our

family.”

FUN SIDE

Joey, from a very young age, took a great interest in the

preparation of the carro. Weeks before, the pieces were taken out from the

camarin or warehouse for polishing, reconstructing, repairing. “Inang would show me the

lace and tissue that she had bought from her trips to Spain and involve me in

the work. She would teach me the way the virgen must be dressed, the

appropriate flowers, the appropriate music that the marching band would play. I

just took to it naturally, it was all a part of my education in the traditions

of the 19th century.”

But such archaic minutae also had a fun side. “Kapampangans are great

eaters, and the day of the fiesta was one big celebration of Bacolor cuisine.

We would wake at dawn to see the formal living room of the old house strewn

with barongs. We would get into them and go to the high Mass. Then, we would

come home to breakfast, a meal to which everyone in town was invited. At

mid-morning, Segundo almuerzo, a heavy merienda was offered to all who had

worked on the carro. Lunch was hectic because all the visitors from Manila would

arrive, and it was a matter of Kapampangan pride that Inang offer them a table

of the very best specialties.

Then, at 3 p.m., another merienda for the

latecomers from Manila. The parade would take place at around seven in the

evening. And when we came home, there was a formal dinner in the main house,

and food for everyone in the grounds below. It was exhausting, and even more so

because at the crack of dawn the next day, my brothers would be herded into the

car for the long drive back to school. I would stay an extra week to clean up

and put everything back into place. My parents were not amused, especially my

father. Looking back, I was really torn between two generations: Inang’s which believed in

tradition, and my own family’s

pragmatism and modernity!”

His mother, the writer Lourdes Abad-Panlilio, once whispered to Joey, just as

the carroza was sweeping past in all its dazzling grandeur, “You must always remember,

hijo, the virgen was a simple woman.”

Joey looks back with little nostalgia and lots of pragmatism.

“It was a feudal

lifestyle, yes. But the one thing I most treasure about it is that it taught us

to deal with everyone from all classes of life. It wasn’t this stereotyped ideal of having caciques and tenants

at your beck and call. Everything was community-based. We worked alongside the

people who worked for us. We decorated the carro together, we ate together, we

marched in the procession together. It was for the Virgin, that was the way we

thought about it. It was a dying tradition even then. But in Bacolor, the

procession was a source of community pride.”

BENIGHTED TRADTION

Sadly as Joey grew into adulthood, he saw the gradual

loss of interest in the benighted tradition. “It needed only the lahar to put an end to the

procession, to that entire way of life.”

Joey and his siblings must have been ready to say goodbye

to it in 1990, when the Pinatubo eruption covered most of Bacolor in lahar. But

Inang Lucing, well into her eighties, had other plans. “I remember I told her that it would be difficult to

organize an evacuation for the furniture and the household effects. She told

me, “What furniture?

All we really need is the carro.”

It dawned on me that this feisty old woman had lived her entire life for only

two things, her family and the virgen. We had to do it.”

Inang, Joey and his brothers and a few friends from

Manila went back in a 10-wheeler truck. “She

rode right up front next to the driver. We went back and tried to save as much

as we could. Everyday, the lahar would rise a little higher, but we finally

managed. On the long ride back, I started to complain. Inang was praying her

rosary, but she stopped to say, “

at least we have somewhere to go. During the war, when I evacuated to the

carro, there was nowhere to go.”

That certainly said a lot about Inang and her character. WE brought everything

back and put it into storage. However, there was no more community, no more old

friends and neighbors. The entire structure that had made the procession come

alive was gone. And there was nothing she could do about that.” Inang Lucing died in 1998,

a shadow of her former self, but still an ardent devotee to the La Naval.

Brother Andrew Gonzalez FSC, former President of De La

Salle University Manila, himself a descendant of the prosperous Arnedo-Gonzalez

clan of Sulipan, Apalit, Pampanga, was no stranger to Kapampangan tradition. “But Brother is one of the

most forward-looking men I’ve

ever met. He admires the past, but he does not live in it. He knew we had saved

all this stuff, he knew that it was in storage. He called me one day and said, “Put all your memories of

childhood into a place where students can learn about them. You have a

responsibility to the future generation. The Museo De La Salle was born.” As envisioned by Brother

Andrew, it would be part of a cultural complex in the 27-Hectare De La Salle

Dasmarinas campus, with the Aklatang Emilio Aguinaldo, the Campus Ministry

Office and the Cavite Studies Center. All of a sudden, Joey who had been a

practicing interior designer, had a new purpose in life. “It was no problem to get

the family donate everything to the new museum. It was the least painful way to

say goodbye to memories.”

WONDERFUL COUPS

Five years into operation, and the Museo De La Salle

located in Dasmarinas, Cavite is not only one of the best-endowed museums in

the country, it is also one of the most talked about. As Executive Director,

Joey has managed some wonderful coups, such as important private donations,

most notably the Guevarra Collection. His old-world tact and diplomacy, coupled

with a wicked charm and serendipity, has gotten the museum many important

bequests from the crème collectors. But it is his florid style of display, so

true to the hyper-refined sensibility of the late 19th century, that make the

museum truly unique.

“Still,” Joey says, “It lacked, in Brother

Andrew Gonzalez FSC’s

words, a spiritual center. Now that the museum is up and running, it seems the

best time to bring out the Virgen again. It has been 14 years since she was

last seen. But this time, it will be in a setting and at a time where she will

give a different meaning to the festivities. And among young people who know

nothing of Bacolor, Pampanga and the past, but who are ready to create their

own traditions.”

When the Virgen de la Naval of Bacolor rides forth again

in the De La Salle Campus in Dasmarinas, Caviteon this month sacred to her and

her devotees, there will be no more caciques and tenants, no proud matrons of

feudal society, no children forced home from school to attend to her. Instead

she will be pulled along by students who have volunteered for the honor of

being her escorts. Perhaps, in Bacolor, she heard very different prayers - for

better crops or kinder masters and cancelled debts. This time the prayers will

be for exams, for careers, for much-needed jobs. No grand fetes, no groaning

tables will mark her fiesta. Only the quiet admiration of a new community that

is beginning something they can call their own. No need now for new jewels and

crowns for this La Naval.