|

| MATER DOLOROSA, COMPLETED |

This Mater Dolorosa, made of antique ivory parts, is without doubt, my favorite because of its personal meaning to me. I was drawn to the Sorrowful Mother at the time my father was battling a fatal disease in 1998. When he passed away, I made a vow to acquire a Dolorosa image to be processed in our town during the Holy Week, in gratitude for his painless, peaceful transition. I managed to find a vintage processional Dolorosa shortly after, and began a family tradition of participating in the annual Semana Santa prusisyons of our town.

ALL WE HAD WAS AN IVORY HEAD... ...AS THE RESTORATION BEGAN.

I also wanted a version that we could venerate at home, perhaps an antique ivory piece, but by the early 2000s, complete, tabletop ivory images were becoming scarcer, and therefore pricier. I started searching for sacred images online—it was something novel at that time—so I was surprised to find an ebay Philippines site that had a few sellers of old items and collectibles.

ANTIQUE HANDS WERE SERENDIPITOUS FINDS. THE HEAD ACQUIRED A CARVED TORSO

It was there that I met a local dealer, who turned out to be the brother of an officemate!. When I asked him offline to be on the lookout for an ivory Dolorosa, he sent a private message to tell me, that he in fact has a solid ivory Dolorosa head. When I got hold of the picture, I was stunned, because it was an antique ivory head some three inches long, exquisitely carved, with open mouth, complete with glass eyes, complete with tiny crystla teardrop. It was of very high quality ivory, creamy white in color, without cracks and flaws. Unfortunately, that was all that he had—the clasped hands are missing, and so is the body, the base (peana), and accessories, right down to lost vestments, metal accessories and wig.

ALL-NEW METAL AUREOLA THE DOLOROSA ON HER PEANA

I just could not pass up this ivory head, so I got it and

kept it in a velvet pouch for a year or so, before I finally took it to my

restorer, Dr. Raffy Lopez. One look, and he confirmed that I, indeed, made a

good decision as the ivory was excellent in all aspects. His only problem were

the missing pair of ivory hands, as it’s almost impossible to find old parts of

appropriate size. I had no choice but to settle for new replacement ivory hands.

FINELY CARVED FACE REVEALS HER GRIEF SALVAGED EMBROIDERY ON HER VESTMENT

DETAIL OF THE FLORAL EMBROIDERY BACK VIEW OF THE CAPE

With my full trust in Dr. Lopez, I just left him to his own devices—although he would contact me once in a while to confer about my personal choices—do I like her in pure black or maroon and blue? Do I prefer a floral peaña? He suggested to do away with the wig as she will be wearing a wimple, anyway. And he also recommended satin fabrics.

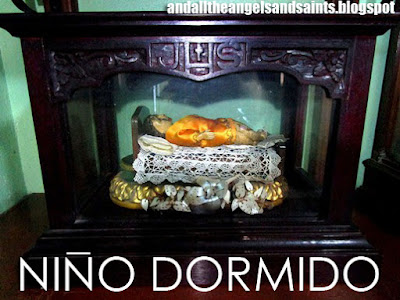

THE COMPLETED IMAGE IS 22 INCHES TALL MATER DOLOROSA, IN HER URNA

While Dr. Lopez was restoring and completing the Dolorosa, I

was also briefing a local carver for a customized urna in which to house my

Dolorosa. Based on the completed height of the image (about 22 inches tall), I commissioned a Betis

artisan to copy a wooden urna and its design, I found in an online antique

site. He had to do it twice—because the first one he did was box shaped; I

wanted the front to have 3 panels of glass, which will make it trapezoidal.

After three months, the antique Dolorosa head had a bastidor body, jointed arms, fully embroidered vestments, and a peana with calado design. It was now a complete image, standing 22 inches tall, beautifully dressed on her gilded base. Inside her carved urna, the Dolorosa reposes, still sad but stunning. Only her new caretaker is sorrowful no more.