|

CANOPY BED FOR A NINO DORMIDO. Made from a trinket box, silver

charms glued together, and other metal scraps. Trimmed with lace. |

The works of young artist King Nicolai Viray are largely unknown except for his postings on his facebook page—and this was where I chanced upon him and his amazing vintage-style sacred art creations that beautifully captured the old-world feel of religious colonial art.

Viray, a fresh 2016 graduate and philosophy major of Mater Boni Consilii in San Fernando, Pampanga is a shy, unassuming 22 year-old, who was drawn to religious arts early.

His artistic leanings may have come from his genes—his maternal grandmother crafted shadow box arts that were taught in Catholic schools at the turn of the 20th century. His paternal grandmother was a Manansala-a relative of national artist Vicente Silva Manansala of Macabebe.

|

A school project, depicting a stained

glass, made from colored cellophanes |

As a kid, Viray drew figures of saints; even his art school projects had religious themes. It was no surprised that his early interest influenced his calling: he was accepted as a seminarian at Pampanga’s premiere seminary, Mother of Good Counsel seminary.

Viray used to visit the Archdiocese Museum in San Fernando, which led to a chance meeting with Msgr. Gene Reyes, then parish priest of Sta. Rita (now with San Fernando), and the museum director.

Msgr. Reyes recalls that Viray was fascinated with the religious shadow box collection there, and so he asked him if could replicate one for his small Sto. Niño. Msgr. Reyes liked what he did and, pretty soon, he asked him to try his hand at some other old paper art forms like quilling (paper roll art). Viray not only mastered that through self-study, but also quickly learned paper fretwork, tole and miniature art. Here is a survey of some of his outstanding vintage-style religious art:

DRAWINGS. Viray’s intricate sketches evoke the style of old religious black and white engravings.

Santos and

santas are his favorite subjects—featured alone or shown enshrined in the altar niches or baldachins.

|

| SAN FERNANDO, pen and ink. |

|

| SAN AGUSTIN DE HIPPO. Pen and ink drawing. |

|

| NTRA. SRA. DE LOS DESAMPARADOS.Pen and ink. |

|

| MATER DOLOROSA. Pen and ink. |

PAPER CUT ART. The art of paper cutting dates back to the 4th century after the Chinese invented paper. Some of their earliest uses for papercutting were for religious decorations or stencils used in holy pictures or estampitas. Several Philippine crafts employ paper cutting-including cut paper fretwork decoration used in Christmas lanterns or

parols.

There is also the art of pabalát (wrapper), where paper is meticulously cut with small scissors to wrap

pastillas (milk candy) and other traditional sweets. During the Victorian age, cutting out silhouettes of people and sceneries became a favorite pastime.

|

VERONICA'S VEIL. replicated antique estampita. Cut and pierced paper,

photocopied image of the Holy Face. |

|

| SAN ANTONIO DE PADUA. Fretwork background from cut paper. |

|

INMACULADA CONCEPCION. Replicated antique lace estampita.

Scanned copy, handcut paper. |

PAPER QUILLING.

Quilling or paper filigree involves the use of strips of paper that are rolled, looped, shaped, and glued together to create decorative patterns and designs. These were used to decorate religious pictures that were then encased in boxes

.

During the Renaissance, European nuns and monks used quilling to decorate book covers and religious items. They used strips of paper trimmed from the gilded edges of books. These gilded paper strips were then rolled to create the quilled shapes. Quilling often imitated the original ironwork of the day.

|

AGNUS DEI PAPER QUILL ART. Cream colored paper strips were rolled and

manipulated into shapes, then glued to form the background for the Lamb of

God paper cutout. |

|

VIRGEN MARIA. Scanned copy of holy picture, with fretwork background,

trimmed with paper roll art and metallic foil flowers. |

|

IVORY NINO. Adorend with quilled paper rolls arranged in floral patterns,

trimmed with lace paper and encased in oval frame. |

RELIGIOUS SHADOW BOXES.A shadow box is a glass-fronted case containing thematic religious object presented in an artistic grouping with artistic grouping. They are the most common example of so-called “monastic” art found in Philippine homes, usually home-made or done as school projects.

The simplest involves decorating prints of religious figures with paper, fabric or mother-of-pearl flowers, accentuated with beads, foil, cork birds and glass. Others entail “dressing up” individual figures by manipulating pieces of fabrics to simulate the folds on their vestments.

Viray’s shadow boxes includes paper tole—in which he cuts and pastes parts of identical religious prints, building up these cutout portions using glue, to create a three-dimensional picture.

|

| ALTAR TABLEAU FOR VIRGEN DE TURUMBA. |

|

SALVADOR DEL MUNDO. Paper cut out of Nino, dressed in folded and

pleated fabrics, surrounded by paper cherubims and paper flowers. |

|

SOLEDAD DE PORTA VAGA 3-DIMENSIONAL ART.

Decorated with assorted plastic gems from craft stores. |

|

| SAN VICENTE FERRER. Tole art, with paper quilling decoration. |

|

STO. TOMAS DE AQUINAS. Paper cutout of

the saint, dressed in real fabrics.Cotton, lace, flowers. |

|

STO NINO DELA PASION. Dressed paper cut-out figure,

old cross pendant. chains. |

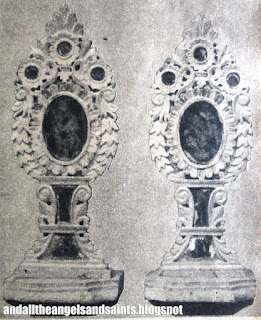

RELIQUARY ART. A reliquary is a container for relics--actual physical remains of saints, such as bones, pieces of clothing, or some object associated with saints or other religious figures. Many relic casings are simple, but when they are presented before an audience, they are encased in magnificent monstrance-like holders. Others are framed in groups, and decorated for display purposes.

|

RELIQUARY MONSTRANCE. Made from the handles of

a silver spoon, old halo, crystal gems, old ribbon brooch. |

|

PAPAL RELICS, with added pictures of Pope John Paul II

and Pope John Paul XXIII and metallic mini-decor. |

SANTOS AND SANTO VESTMENTS. Another hobby of Viray is fashioning and dressing up santos—many received as gifts from friends. Some of these

santos are commercially made, but this does not deter him from giving free rein to his creativity, while sticking to dressing traditions.

|

LORETTO KINDLEIN OF SALZBURG. A Nino replica of the Holy Child

of Salzburg, Germany. |

|

VIRGEN DE CAYSASAY. A resin image of Our Lady of Caysasay was placed

on a gilt base, wigged and dressed with acape trimmed with appliques. |

|

STA. MARIA MAGDALENA DE NAGASAKI. Ingeniously

fashioned from an Japan surplus Japanese doll. |

|

PADRE PIO. A wooden figure of the stigmatic saint dressed in a

chasuble and alb. |

MINIATURES. Viray has managed to replicate retablos (church altars) in miniature, using available materials—resin statues of saints, wood, cardboard, foil and paper scraps.

|

RETABLO MAYOR. A main altar made from cardboard, wood,

and other paper trims. Small iamges are store-bought. |

Of late, the young artist has been accepting a limited number of commissions, despite his busy schedule. He is currently taking his regency (time off from the seminary ) and is working at the local DPWH as administrative aide. Meanwhile, Viray continues to amaze his facebook friends (and fans) with his regular postings of his creations. His body of work is very impressive, considering that he does these beautiful objects in his spare time, and only at his leisure.

|

| CHURCH BANNER. Sta. Maria de Cabeza. |

What’s more extraordinary is his use of everyday materials and found objects to create exquisite treasures. In his hands, cheap charms bought from Divisoria become decorations for a

Niño Dormido’s canopy bed, while a silver-colored plastic container is transformed into an elegant

santo base. Even plain paper, when painstakingly pierced and cut by Viray, becomes a delicate lace background for

estampitas. His works are destined to be priceless treasures, worthy to be collected and enjoyed.

Indeed, the future of devotional art looms bright, thanks to the amazing gift of King Nikolai Viray.